Infection with the larval form of Echinococcus multilocularis causes alveolar echinococcosis (AE). The infection behaves as a slow-growing malignant tumor. Initially, it is located in the liver and then may spread to any other organ through metastases.

Without appropriate therapeutic management, the infection is lethal.

Echinococci are platyhelminths of the cestode genus. The parasitic cycle of the organism involves definitive hosts and intermediate hosts, each harboring different stages of the parasite life cycle.

Carnivores are the definitive hosts for the adult form of the parasite, which is an intestinal worm also termed taenia. Numerous (ie, tens to thousands) adult worms that average 2-5 mm in length live in the small bowel of carnivores (taeniasis) and are attached to the small bowel mucosa by hooks and suckers.

After 25-40 days, the worm's last gravid segment, each containing hundreds of microscopic eggs (6-hooked oncospheres or hexacanth embryos, 30-40 mm in diameter), detaches from the nonfertile segments. The egg-containing segments are then dispersed through the feces of the carnivore.

Various species act as intermediate hosts, serving the larval form of the parasite (ie, metacestode). The metacestode is a continuously growing tumorlike polycystic mass that is not clearly separated from host tissues.

The larval-stage parasite is composed of vesicles that become fertile by producing a form termed the protoscolex, which is able to recreate the adult worm in the definitive host. The protoscoleces that fill the vesicles transform into adult worms once ingested into the intestine of the carnivore host.

The cycle of E multilocularis in Europe is predominantly sylvatic, involving red foxes (see image below) as definitive hosts and rodents as intermediate hosts. In some countries, dogs and cats have been identified as definitive hosts; however, all definitive host species acquire the infection from the sylvatic cycle by consuming rodents infected with metacestodes of E multilocularis. In Alaska and in the People's Republic of China, the domestic cycle, involving family or stray dogs, is particularly important.

E multilocularis eggs, which are the infectious agents for humans, are dispersed in the environment via the feces of carnivores. The eggs may contaminate various types of food, including fruits and vegetables collected from gardens or infected meadows, and drinking water. An oncosphere membrane protects Echinococcus eggs, making them extremely tolerant of environmental conditions. E multilocularis eggs may remain infectious at temperatures ranging from -30°C to +60°C. They are easily destroyed by heat but may survive months or years at low temperatures, especially if they are protected against drying. Freezing the eggs at -20°C does not affect their infectious potency.

Simultaneous occurrence of both alveolar echinococcosis and cystic echinococcosis resulting from Echinococcus granulosus infection is extremely rare but has occurred in endemic areas where both species are present in the environment (eg, western China).

Pathophysiology

Alveolar echinococcosis is a chronic disease with a presymptomatic stage that may last for years before signs and symptoms develop. The variability of the signs and symptoms depends on the location of the lesions (see image below), which may develop in the liver and/or in various organs or tissues, especially the lungs, brain, and bones.

E multilocularis larvae grow as tumorlike buds that transform into multiple vesicles filled with fluid and, in 15% of cases, with protoscoleces. The parasitic vesicles are lined with a germinal layer and a laminated layer, which are immediately surrounded by an exuberant granulomatous response generated by the host's immune system. This reaction has two main consequences, fibrosis and necrosis (see image below).

Both reactions protect the host against larval growth but may also be deleterious.

Fibrosis in alveolar echinococcosis is extremely active from the beginning of the infection.

Irreversible acellular fibrosis composed of cross-linked collagens ensues and isolates the parasitic lesions from the host but also compresses and obstructs major vessels and bile ducts. Noncaseous necrosis in the center of the lesions may be superinfected by bacteria and fungi, possibly leading to complications (eg, liver abscesses, septicemia).

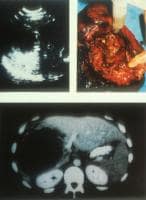

Ultrasonographic, CT scan, and perioperative aspect of a typical lesion of alveolar echinococcosis with central necrosis. Courtesy of Jean-Philippe Miguet, MD.

Similar to several other parasitic diseases, alveolar echinococcosis appears as a polar disease (as defined inleprosy).

The ability of the organism to infect a host and the severity of disease once successfully inoculated depend on the receptivity of the host (ie, host immune defenses).

Mass screenings prove that abortive forms (see image below) exist and may occur in most cases, explaining the relatively low prevalence of this disease. Experimental studies in infected mice and immunologic studies in humans reveal the importance of cell-mediated immunity in the control of larval growth. Immune responses, characterized by a helper T cell TH 1 profile of cytokine secretion, can kill the larvae, thus protecting the host. The progressive forms of the disease are characterized by a TH 2 profile consisting of increased interleukin (IL)–10, transforming growth factor (TGF)–beta, and IL-5 secretion.

Frequency

United States

Foxes infected with E multilocularis are present in most of the northern and central states. The organism has been observed in all or parts of 11 contiguous states and 3 adjacent Canadian provinces in an area centered by southern Manitoba and North Dakota. However, only 2 cases involving humans living in this area have been described since the beginning of the 20th century. Transport of infected foxes from endemic areas to eastern and southern states for hunting purposes could create new areas at risk of becoming endemic. In Alaska, alveolar echinococcosis is observed in Eskimos, especially on St. Lawrence Island, where 30 of 53 cases were diagnosed in Alaska from 1947-1990.

International

Alveolar echinococcosis occurs only in the northern hemisphere, in geographically limited foci (endemic areas) of west-central Europe, Turkey, most areas of the former Soviet Union, Iran, Iraq, western and central China, and northern Japan (Hokkaido Island). If considering only at-risk rural populations in regions in central Europe that are endemic for alveolar echinococcosis, the incidence is 1-20 cases per 100,000 persons per year, despite an overall country prevalence that may be very low. In endemic foci of China, prevalence averages 5% but may reach 10% in villages with specific risk factors. The prevalence of E multilocularis infection in foxes is 15-70% in endemic areas.

Recent trends are related to increasing percentages of infected foxes and increased distribution of those foxes. The presence of infected foxes in large cities of Europe and northern Japan is now well documented; 10% (in city centers) to 50% (in the suburbs) may be found in cities of the European endemic areas (such as Zurich or Geneva in Switzerland, Stuttgart in Germany, or Nancy in France). This and a newly recognized trend of infection in dogs and cats in endemic areas in Europe may lead to major changes in the human populations at risk in the near future.

Mortality/Morbidity

Untreated alveolar echinococcosis is usually fatal. The survival rate at 5 years in untreated patients averages 40%. Therapeutic approaches that have been developed since the early 1980s have markedly improved the prognosis of the disease. The actuarial survival rate at 5 years was 88% in a series of 80 patients observed from 1983-1993.

tags:Echinococcosis,infected,

Infection with the larval form of Echinococcus multilocularis causes alveolar echinococcosis (AE). The infection behaves as a slow-growing malignant tumor. Initially, it is located in the liver and then may spread to any other organ through metastases.

Without appropriate therapeutic management, the infection is lethal.

Echinococci are platyhelminths of the cestode genus. The parasitic cycle of the organism involves definitive hosts and intermediate hosts, each harboring different stages of the parasite life cycle.

Carnivores are the definitive hosts for the adult form of the parasite, which is an intestinal worm also termed taenia. Numerous (ie, tens to thousands) adult worms that average 2-5 mm in length live in the small bowel of carnivores (taeniasis) and are attached to the small bowel mucosa by hooks and suckers.

After 25-40 days, the worm's last gravid segment, each containing hundreds of microscopic eggs (6-hooked oncospheres or hexacanth embryos, 30-40 mm in diameter), detaches from the nonfertile segments. The egg-containing segments are then dispersed through the feces of the carnivore.

Various species act as intermediate hosts, serving the larval form of the parasite (ie, metacestode). The metacestode is a continuously growing tumorlike polycystic mass that is not clearly separated from host tissues.

The larval-stage parasite is composed of vesicles that become fertile by producing a form termed the protoscolex, which is able to recreate the adult worm in the definitive host. The protoscoleces that fill the vesicles transform into adult worms once ingested into the intestine of the carnivore host.

The cycle of E multilocularis in Europe is predominantly sylvatic, involving red foxes (see image below) as definitive hosts and rodents as intermediate hosts. In some countries, dogs and cats have been identified as definitive hosts; however, all definitive host species acquire the infection from the sylvatic cycle by consuming rodents infected with metacestodes of E multilocularis. In Alaska and in the People's Republic of China, the domestic cycle, involving family or stray dogs, is particularly important.

E multilocularis eggs, which are the infectious agents for humans, are dispersed in the environment via the feces of carnivores. The eggs may contaminate various types of food, including fruits and vegetables collected from gardens or infected meadows, and drinking water. An oncosphere membrane protects Echinococcus eggs, making them extremely tolerant of environmental conditions. E multilocularis eggs may remain infectious at temperatures ranging from -30°C to +60°C. They are easily destroyed by heat but may survive months or years at low temperatures, especially if they are protected against drying. Freezing the eggs at -20°C does not affect their infectious potency.

Simultaneous occurrence of both alveolar echinococcosis and cystic echinococcosis resulting from Echinococcus granulosus infection is extremely rare but has occurred in endemic areas where both species are present in the environment (eg, western China).

Pathophysiology

Alveolar echinococcosis is a chronic disease with a presymptomatic stage that may last for years before signs and symptoms develop. The variability of the signs and symptoms depends on the location of the lesions (see image below), which may develop in the liver and/or in various organs or tissues, especially the lungs, brain, and bones.

E multilocularis larvae grow as tumorlike buds that transform into multiple vesicles filled with fluid and, in 15% of cases, with protoscoleces. The parasitic vesicles are lined with a germinal layer and a laminated layer, which are immediately surrounded by an exuberant granulomatous response generated by the host's immune system. This reaction has two main consequences, fibrosis and necrosis (see image below).

Both reactions protect the host against larval growth but may also be deleterious.

Fibrosis in alveolar echinococcosis is extremely active from the beginning of the infection.

Irreversible acellular fibrosis composed of cross-linked collagens ensues and isolates the parasitic lesions from the host but also compresses and obstructs major vessels and bile ducts. Noncaseous necrosis in the center of the lesions may be superinfected by bacteria and fungi, possibly leading to complications (eg, liver abscesses, septicemia).

Infection with the larval form of Echinococcus multilocularis causes alveolar echinococcosis (AE). The infection behaves as a slow-growing malignant tumor. Initially, it is located in the liver and then may spread to any other organ through metastases.

Without appropriate therapeutic management, the infection is lethal.

Without appropriate therapeutic management, the infection is lethal.

Echinococci are platyhelminths of the cestode genus. The parasitic cycle of the organism involves definitive hosts and intermediate hosts, each harboring different stages of the parasite life cycle.

Carnivores are the definitive hosts for the adult form of the parasite, which is an intestinal worm also termed taenia. Numerous (ie, tens to thousands) adult worms that average 2-5 mm in length live in the small bowel of carnivores (taeniasis) and are attached to the small bowel mucosa by hooks and suckers.

After 25-40 days, the worm's last gravid segment, each containing hundreds of microscopic eggs (6-hooked oncospheres or hexacanth embryos, 30-40 mm in diameter), detaches from the nonfertile segments. The egg-containing segments are then dispersed through the feces of the carnivore.

After 25-40 days, the worm's last gravid segment, each containing hundreds of microscopic eggs (6-hooked oncospheres or hexacanth embryos, 30-40 mm in diameter), detaches from the nonfertile segments. The egg-containing segments are then dispersed through the feces of the carnivore.

Various species act as intermediate hosts, serving the larval form of the parasite (ie, metacestode). The metacestode is a continuously growing tumorlike polycystic mass that is not clearly separated from host tissues.

The larval-stage parasite is composed of vesicles that become fertile by producing a form termed the protoscolex, which is able to recreate the adult worm in the definitive host. The protoscoleces that fill the vesicles transform into adult worms once ingested into the intestine of the carnivore host.

The cycle of E multilocularis in Europe is predominantly sylvatic, involving red foxes (see image below) as definitive hosts and rodents as intermediate hosts. In some countries, dogs and cats have been identified as definitive hosts; however, all definitive host species acquire the infection from the sylvatic cycle by consuming rodents infected with metacestodes of E multilocularis. In Alaska and in the People's Republic of China, the domestic cycle, involving family or stray dogs, is particularly important.

E multilocularis eggs, which are the infectious agents for humans, are dispersed in the environment via the feces of carnivores. The eggs may contaminate various types of food, including fruits and vegetables collected from gardens or infected meadows, and drinking water. An oncosphere membrane protects Echinococcus eggs, making them extremely tolerant of environmental conditions. E multilocularis eggs may remain infectious at temperatures ranging from -30°C to +60°C. They are easily destroyed by heat but may survive months or years at low temperatures, especially if they are protected against drying. Freezing the eggs at -20°C does not affect their infectious potency.

Simultaneous occurrence of both alveolar echinococcosis and cystic echinococcosis resulting from Echinococcus granulosus infection is extremely rare but has occurred in endemic areas where both species are present in the environment (eg, western China).

Pathophysiology

Alveolar echinococcosis is a chronic disease with a presymptomatic stage that may last for years before signs and symptoms develop. The variability of the signs and symptoms depends on the location of the lesions (see image below), which may develop in the liver and/or in various organs or tissues, especially the lungs, brain, and bones.

E multilocularis larvae grow as tumorlike buds that transform into multiple vesicles filled with fluid and, in 15% of cases, with protoscoleces. The parasitic vesicles are lined with a germinal layer and a laminated layer, which are immediately surrounded by an exuberant granulomatous response generated by the host's immune system. This reaction has two main consequences, fibrosis and necrosis (see image below).

Both reactions protect the host against larval growth but may also be deleterious.

Fibrosis in alveolar echinococcosis is extremely active from the beginning of the infection.

Irreversible acellular fibrosis composed of cross-linked collagens ensues and isolates the parasitic lesions from the host but also compresses and obstructs major vessels and bile ducts. Noncaseous necrosis in the center of the lesions may be superinfected by bacteria and fungi, possibly leading to complications (eg, liver abscesses, septicemia).

Irreversible acellular fibrosis composed of cross-linked collagens ensues and isolates the parasitic lesions from the host but also compresses and obstructs major vessels and bile ducts. Noncaseous necrosis in the center of the lesions may be superinfected by bacteria and fungi, possibly leading to complications (eg, liver abscesses, septicemia).

Ultrasonographic, CT scan, and perioperative aspect of a typical lesion of alveolar echinococcosis with central necrosis. Courtesy of Jean-Philippe Miguet, MD.

Similar to several other parasitic diseases, alveolar echinococcosis appears as a polar disease (as defined inleprosy).

The ability of the organism to infect a host and the severity of disease once successfully inoculated depend on the receptivity of the host (ie, host immune defenses).

Mass screenings prove that abortive forms (see image below) exist and may occur in most cases, explaining the relatively low prevalence of this disease. Experimental studies in infected mice and immunologic studies in humans reveal the importance of cell-mediated immunity in the control of larval growth. Immune responses, characterized by a helper T cell TH 1 profile of cytokine secretion, can kill the larvae, thus protecting the host. The progressive forms of the disease are characterized by a TH 2 profile consisting of increased interleukin (IL)–10, transforming growth factor (TGF)–beta, and IL-5 secretion.

Frequency

United States

Foxes infected with E multilocularis are present in most of the northern and central states. The organism has been observed in all or parts of 11 contiguous states and 3 adjacent Canadian provinces in an area centered by southern Manitoba and North Dakota. However, only 2 cases involving humans living in this area have been described since the beginning of the 20th century. Transport of infected foxes from endemic areas to eastern and southern states for hunting purposes could create new areas at risk of becoming endemic. In Alaska, alveolar echinococcosis is observed in Eskimos, especially on St. Lawrence Island, where 30 of 53 cases were diagnosed in Alaska from 1947-1990.

International

Alveolar echinococcosis occurs only in the northern hemisphere, in geographically limited foci (endemic areas) of west-central Europe, Turkey, most areas of the former Soviet Union, Iran, Iraq, western and central China, and northern Japan (Hokkaido Island). If considering only at-risk rural populations in regions in central Europe that are endemic for alveolar echinococcosis, the incidence is 1-20 cases per 100,000 persons per year, despite an overall country prevalence that may be very low. In endemic foci of China, prevalence averages 5% but may reach 10% in villages with specific risk factors. The prevalence of E multilocularis infection in foxes is 15-70% in endemic areas.

Recent trends are related to increasing percentages of infected foxes and increased distribution of those foxes. The presence of infected foxes in large cities of Europe and northern Japan is now well documented; 10% (in city centers) to 50% (in the suburbs) may be found in cities of the European endemic areas (such as Zurich or Geneva in Switzerland, Stuttgart in Germany, or Nancy in France). This and a newly recognized trend of infection in dogs and cats in endemic areas in Europe may lead to major changes in the human populations at risk in the near future.

Mortality/Morbidity

Untreated alveolar echinococcosis is usually fatal. The survival rate at 5 years in untreated patients averages 40%. Therapeutic approaches that have been developed since the early 1980s have markedly improved the prognosis of the disease. The actuarial survival rate at 5 years was 88% in a series of 80 patients observed from 1983-1993.

No comments:

Post a Comment